Bacon Nutrition Facts: Dietitian Insights

Bacon has become a controversial food in modern nutrition discourse, simultaneously celebrated by low-carb diet enthusiasts and scrutinized by health professionals concerned about saturated fat and sodium content. Understanding the complete nutritional profile of bacon requires moving beyond simplistic judgments to examine what this cured meat actually contains, how it affects different dietary patterns, and how it fits into a balanced approach to eating. This comprehensive guide breaks down the science behind bacon nutrition with insights from dietitian perspectives and contemporary research.

Whether you enjoy bacon as an occasional indulgence or incorporate it regularly into your meals, knowing the facts empowers you to make informed dietary choices aligned with your personal health goals. The conversation around bacon nutrition has evolved significantly, and modern dietary science offers nuanced perspectives that go beyond the “good food” versus “bad food” binary that dominated earlier nutritional guidance.

Complete Nutritional Breakdown Per Serving

A standard serving of bacon consists of two medium slices (approximately 14 grams cooked), which provides roughly 80-90 calories depending on the cooking method and fat content of the specific product. This foundational serving size serves as the reference point for all nutritional information typically listed on bacon packaging and used in dietary recommendations. Understanding this baseline helps consumers accurately track their intake when incorporating bacon into meal plans or tracking nutritional goals.

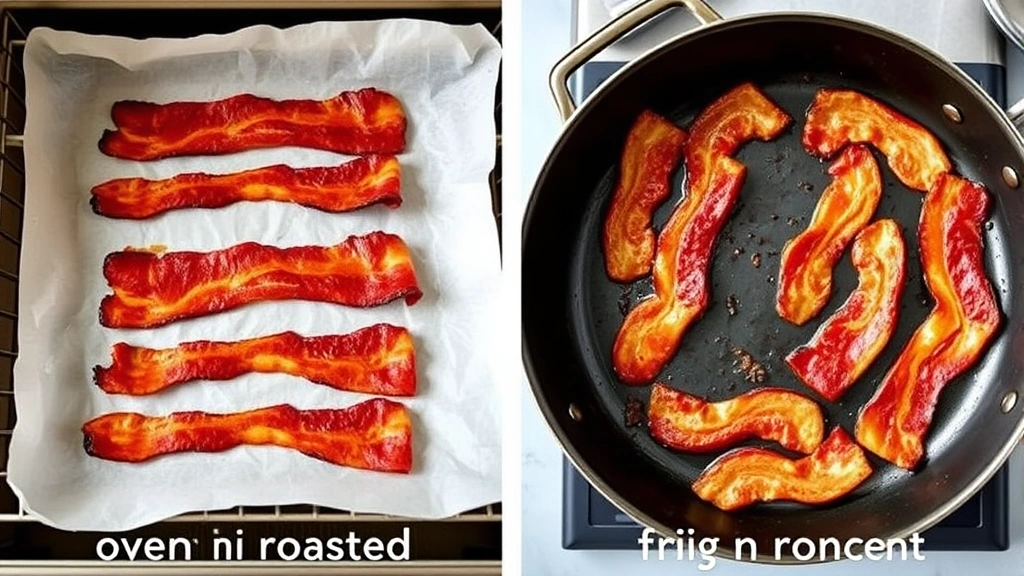

The nutritional composition varies slightly based on whether bacon is pan-fried, oven-roasted, or microwaved, with cooking method affecting the final fat content and caloric density. Two slices of cooked bacon typically contain approximately 6-7 grams of fat, 6 grams of protein, and negligible carbohydrates. These macronutrient ratios make bacon particularly popular among followers of low-carbohydrate nutrition plans, where the protein-to-carb ratio becomes a critical consideration for meal composition.

Beyond the basic macronutrients, bacon contains B vitamins including thiamine, riboflavin, niacin, and B6, which play essential roles in energy metabolism and nervous system function. The presence of these vitamins, combined with minerals like phosphorus and selenium, contributes to bacon’s micronutrient profile. However, the quantities of these nutrients per serving are relatively modest compared to other protein sources, which is an important consideration when evaluating bacon’s nutritional efficiency within a broader dietary context.

Macronutrient Analysis and Caloric Content

From a macronutrient perspective, bacon represents a high-fat, moderate-protein food with essentially zero carbohydrates. The fat composition in bacon is particularly noteworthy, consisting of approximately 50% monounsaturated fat, 40% saturated fat, and 10% polyunsaturated fat, though these ratios can vary based on the pig’s diet and the specific cut of meat used. This fat distribution differs from many other animal proteins and contributes significantly to bacon’s unique nutritional profile and its role in various dietary frameworks.

The protein content in bacon, while respectable at about 6 grams per two-slice serving, comes with substantial fat calories, making bacon a less protein-efficient choice compared to leaner protein sources like chicken breast or fish. However, the combination of protein and fat provides satiety benefits that some individuals find valuable for appetite management and meal satisfaction. When incorporated into strategic meal planning, bacon’s satiating properties can support portion control and reduce overall calorie consumption throughout the day.

The caloric density of bacon—approximately 5.7 calories per gram—means that portion control becomes particularly important for individuals monitoring total energy intake for weight management. A serving of bacon delivers roughly 80-90 calories in a relatively small physical volume, which contrasts with lower-calorie-density foods that provide similar satiety with fewer calories. Understanding this concentration of calories helps consumers integrate bacon appropriately into calorie-controlled dietary approaches.

Micronutrients and Mineral Content

Beyond macronutrients, bacon provides several important micronutrients that contribute to overall nutritional value. Selenium content in bacon is particularly significant, with two slices providing approximately 15-20% of the daily recommended intake. Selenium functions as a crucial cofactor for antioxidant enzymes and plays vital roles in thyroid hormone metabolism and immune system regulation. This mineral contribution, while often overlooked, represents one of bacon’s more substantial nutritional assets.

Phosphorus content in bacon is substantial, with each serving contributing significantly toward the daily recommended intake of this mineral essential for bone health and energy metabolism. Bacon also provides bioavailable forms of iron, though in quantities less impressive than red meat alternatives. The heme iron present in bacon (the more readily absorbed form compared to plant-based iron) makes it particularly valuable for individuals managing iron status, especially those following plant-forward diets who may benefit from occasional animal protein sources.

Choline, a nutrient often grouped with B vitamins, appears in meaningful quantities in bacon. This compound plays important roles in liver function, brain health, and muscle metabolism. While not typically highlighted in nutritional discussions of bacon, choline represents an underappreciated micronutrient contribution that aligns with emerging research on optimal nutrition for cognitive function and metabolic health. For individuals interested in nutrition and mental health optimization, these micronutrient contributions warrant consideration.

Sodium and Processed Meat Concerns

Perhaps the most significant nutritional concern regarding bacon centers on its sodium content. A single serving of two medium slices contains approximately 310-380 milligrams of sodium, representing roughly 13-16% of the daily recommended maximum intake. For individuals managing hypertension or following sodium-restricted diets for cardiovascular health reasons, this sodium concentration requires careful consideration and portion management. The curing process that creates bacon’s characteristic flavor necessarily involves salt, making sodium reduction fundamentally challenging without compromising the product’s identity.

The processed meat classification assigned to bacon by health organizations including the World Health Organization reflects concerns about nitrates, nitrites, and other preservation compounds used in the curing process. Research published through peer-reviewed epidemiological studies has associated processed meat consumption with increased risk of colorectal cancer, though the absolute risk increase remains modest and depends on consumption frequency and quantity. Understanding these associations helps contextualize bacon within broader dietary patterns rather than viewing it as an isolated food item.

Nitrates and nitrites, while concerning to some consumers, serve important food safety functions by preventing botulism and other bacterial contamination. Interestingly, the body converts dietary nitrates into nitric oxide, which provides vascular benefits in some contexts, complicating the simplistic narrative that all nitrates represent harmful compounds. The distinction between processed meat consumption as an occasional dietary component versus a dietary staple significantly influences the magnitude of associated health risks, making frequency and context crucial considerations.

Saturated Fat Profile and Heart Health

The saturated fat content in bacon—approximately 2.4 grams per two-slice serving—has historically generated concerns about cardiovascular health. However, contemporary nutritional science has become increasingly nuanced regarding saturated fat, recognizing that the relationship between saturated fat consumption and heart disease risk is more complex than earlier models suggested. The specific type of saturated fat, the overall dietary pattern, and individual metabolic factors all influence how bacon’s saturated fat affects cardiovascular health outcomes.

Recent research indicates that the cardiovascular impact of bacon depends substantially on what foods it replaces in the diet. When bacon substitutes for refined carbohydrates or ultra-processed foods, the overall dietary quality may actually improve. Conversely, when bacon consumption increases total caloric intake or displaces nutrient-dense whole foods, cardiovascular risk markers may worsen. This context-dependent relationship underscores the importance of viewing bacon within the framework of complete dietary patterns rather than as an isolated nutrient consideration.

The presence of myristic acid and palmitic acid in bacon’s saturated fat composition deserves specific attention, as these fatty acids demonstrate different cardiovascular effects compared to stearic acid, which is metabolically neutral regarding cholesterol. The lipid profile changes from bacon consumption appear modest for most individuals following otherwise balanced diets, particularly when bacon intake remains moderate and occasional rather than daily and excessive.

Bacon in Different Dietary Approaches

Within ketogenic and low-carbohydrate dietary frameworks, bacon occupies a prominent nutritional role due to its zero-carbohydrate profile and favorable macronutrient ratios for ketone production. The combination of fat and protein with complete carbohydrate absence makes bacon an efficient food for maintaining ketosis and supporting satiety during carbohydrate restriction. Many individuals following these dietary approaches incorporate bacon regularly as a staple protein source, and for this population, understanding bacon’s complete nutritional profile becomes particularly important for optimizing health outcomes.

In Mediterranean and other traditional dietary patterns emphasizing plant-forward eating, bacon appears less frequently and in smaller quantities, typically used as a flavoring agent rather than a primary protein source. This approach allows consumers to benefit from bacon’s flavor and micronutrient contributions while maintaining overall dietary patterns associated with longevity and disease prevention. The distinction between bacon as a dietary staple versus bacon as an occasional flavor enhancer significantly influences its health implications.

For individuals following higher-protein dietary approaches focused on muscle building and athletic performance, bacon’s protein content alone makes it a relatively inefficient choice compared to leaner alternatives, though the combination of protein and fat may provide benefits for certain training phases. Athletes and fitness enthusiasts typically incorporate bacon occasionally while prioritizing leaner protein sources for the majority of protein needs, balancing flavor preferences with performance optimization.

Healthier Preparation Methods

The cooking method used for bacon preparation significantly influences its final nutritional composition and potential health implications. Oven-roasting at 400°F for approximately 15-20 minutes represents one of the healthiest preparation approaches, as it allows fat to drain away while maintaining even cooking and preventing the high-temperature charring that occurs with pan-frying. This method also reduces the formation of heterocyclic amines and other compounds potentially formed during high-heat cooking, making it preferable from a food safety perspective.

Microwaving bacon on paper towels provides another relatively healthy preparation option, as the microwave’s lower cooking temperature and the paper towels’ fat-absorption capacity reduce the final fat content without requiring active monitoring. While some consumers object to microwaved bacon’s texture compared to traditional methods, the reduced fat absorption and lower cooking temperatures offer nutritional advantages worth considering, particularly for individuals managing fat intake or seeking to optimize nutrient absorption and metabolic efficiency.

Conversely, deep-frying bacon or cooking it in butter significantly increases fat absorption and caloric content, transforming bacon from a moderate-calorie protein source into a high-calorie indulgence. Similarly, pan-frying without draining grease allows bacon to reabsorb rendered fat, increasing the final product’s fat and calorie content substantially. Conscious selection of cooking methods represents one of the most straightforward ways to modify bacon’s nutritional impact without eliminating it from the diet entirely.

Portion Control and Moderation Strategies

For individuals seeking to incorporate bacon into a health-conscious diet, establishing clear portion guidelines becomes essential. Rather than eliminating bacon entirely, defining a specific serving size—such as limiting intake to 2-3 servings per week—allows enjoyment while managing cumulative sodium and saturated fat intake. This moderation approach aligns with broader principles of sustainable dietary change, as overly restrictive approaches often prove difficult to maintain long-term.

Strategic incorporation of bacon into meals can enhance overall dietary quality by improving satiety and satisfaction with meals, potentially reducing overall calorie consumption and supporting weight management goals. Using bacon as a flavor-enhancing ingredient in vegetable dishes or salads allows consumers to benefit from its taste and micronutrient contributions while maintaining appropriate portion sizes. This approach—treating bacon as a seasoning or accent rather than the meal’s primary component—optimizes both nutritional balance and dietary sustainability.

Pairing bacon with high-fiber foods and abundant vegetables creates a more balanced nutritional profile and improves satiety compared to consuming bacon alone or with refined carbohydrates. The synergistic combination of bacon’s fat and protein with fiber-rich vegetables creates meals with superior satiety and blood sugar stability compared to bacon consumed in isolation or with processed foods. This strategic food combining approach exemplifies how understanding individual food nutrition allows for optimization within broader comprehensive nutrition guidance.

Tracking bacon consumption over weeks rather than focusing on individual days helps contextualize intake within realistic dietary patterns. Many individuals find that allowing occasional bacon enjoyment within a structured framework proves more sustainable than rigid elimination, supporting long-term adherence to health-promoting dietary patterns. This flexible, context-aware approach to bacon consumption reflects modern nutritional science’s emphasis on sustainable behavioral change over perfectionist dietary restriction.

FAQ

How many calories are in a serving of bacon?

A standard serving of two medium slices of cooked bacon contains approximately 80-90 calories, with variation depending on cooking method and the specific product’s fat content. Oven-roasted bacon typically contains fewer calories than pan-fried bacon due to greater fat drainage during cooking.

Is bacon high in protein?

Bacon provides approximately 6 grams of protein per two-slice serving, which is moderate compared to other protein sources. While respectable, bacon’s protein efficiency is lower than leaner alternatives like chicken breast or fish, though the combination of protein and fat provides superior satiety for many individuals.

Can I eat bacon on a low-carb diet?

Yes, bacon is an excellent choice for low-carbohydrate and ketogenic diets due to its zero-carbohydrate profile and favorable macronutrient ratios. However, monitoring sodium and saturated fat intake remains important even within low-carb dietary frameworks.

What is the sodium content in bacon?

Two slices of bacon contain approximately 310-380 milligrams of sodium, representing roughly 13-16% of the daily recommended maximum. Individuals managing hypertension should monitor bacon consumption carefully and balance it with lower-sodium foods.

Does the cooking method affect bacon’s nutrition?

Yes, cooking method significantly influences bacon’s final nutritional composition. Oven-roasting and microwaving produce lower-fat products compared to pan-frying or deep-frying, as these methods allow greater fat drainage and reduce fat reabsorption.

Is bacon considered a processed meat?

Yes, bacon is classified as a processed meat due to its curing process involving salt and preservation compounds. Epidemiological research suggests associations between processed meat consumption and certain health conditions, though absolute risk depends on consumption frequency and quantity.

What micronutrients does bacon provide?

Bacon provides significant quantities of selenium, phosphorus, and choline, along with B vitamins including thiamine, riboflavin, and niacin. It also provides bioavailable heme iron, though in quantities less impressive than other red meat sources.

How much bacon can I safely eat weekly?

Health organizations generally suggest limiting processed meat consumption to occasional intake rather than daily consumption. For most individuals, 2-3 servings per week represents a reasonable moderation threshold, though individual tolerance depends on overall dietary patterns and health status.